Markets are good for a lot of things. They have an irrefutable ability to cater to our demands, how seemingly ridiculous our demands might be. Think about silly putty. If enough people want it, they will get it. But there is a catch. You must be able to afford it. You can desire as much silly putty you want but if you can’t afford it or there isn’t demand from enough people to bring the per unit cost down for you to afford it, the market won’t deliver.

The same limitation of market translates to a bigger problem for development practitioners. This means that if there is a demand for an essential product such as a vaccine from the cash-strapped developing countries, but there isn’t demand for the same product from wealthier potential customers in the developed countries. The market won’t deliver.

This means that there is a deficit of incentives for the market to provide a product to people who can’t afford it. In the case of vaccine’s, the challenge seems to be startling. The development of vaccines could save millions of lives, but pharmaceutical companies don’t have the incentive to put their money in research of these vaccines when there is little economic return.

In a recent guest lecture at the London School of Economics, economist Owen Barder asked students to guess how much does the world spend seeking a cure for malaria in comparison to the global spending to cure male baldness.

The answer, which most of us guessed correctly, is about a tenth.

The reason is simple, pharmaceutical companies can’t offset the cost of developing malaria vaccine to the consumers unlike whatever remedy it develops for male baldness. “So, these companies are already taking the risk for rich countries who can pay more, but not for poor states who may not,” Owen says.

The solution? Manipulating the markets so the vaccines demanded by lower-income countries work in a similar manner that those demanded by richer countries. This intuition made the basses of a 2005 reportby the Centre for Global Development, which Owen co-authored.

“Barely 10% of global R&D is devoted to diseases that affect 90% of the world’s population,” the report notes.

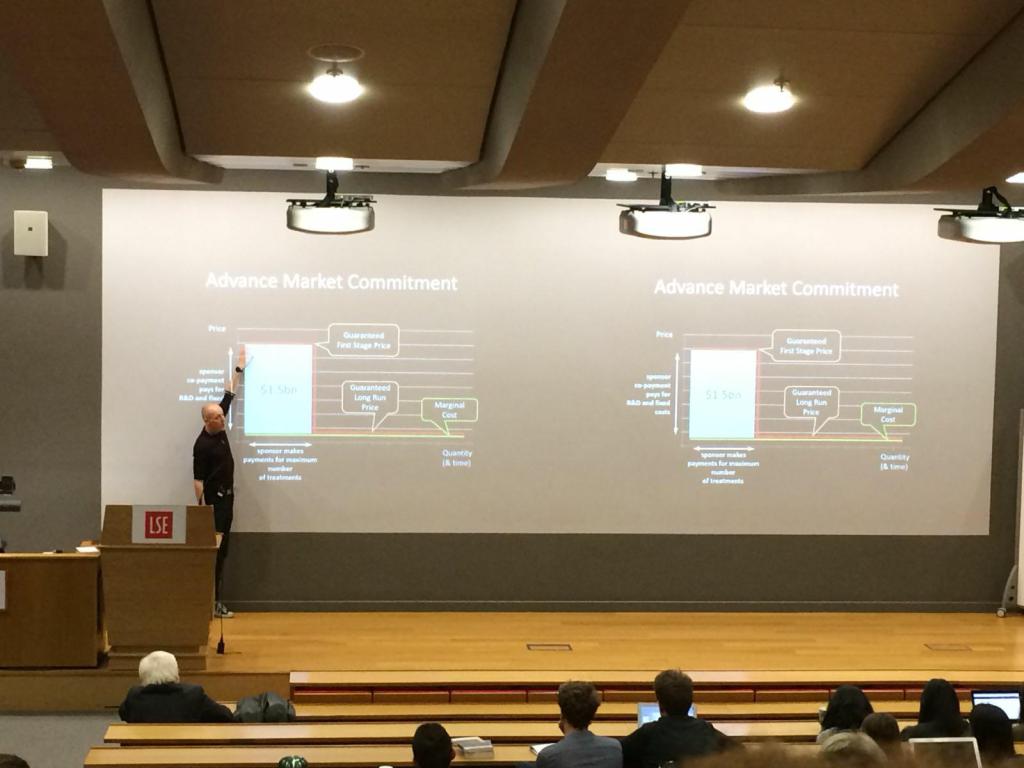

The report proposed that the global donors to make an “advance market commitment (or AMC)” to pay for a certain number of successful pneumococcal vaccines, in turn offsetting research and development costs which the pharmaceutical companies would bear. “If it (vaccine) doesn’t work, it doesn’t cost us (the donors) anything.”

The idea is strikingly simple. Instead of spending the money on sponsoring research for the vaccine, donors enter into a legal agreement with pharmaceutical companies for purchasing a number of vaccine in advance at a price high enough to incentivize companies to invest in research, in turn subsidising developing countries to save lives.

When Owen and his colleagues told donors about the idea, the response was similar “it is such a good idea that somebody might have already done it.”

The concept was luring enough that within months the G7 Finance Ministers backed the proposal in a conference in London. In 2009, this led to five countries, along with the Gates Foundation, to commit to $1.5 billion for a vaccine for pneumococcal diseases which, in 2005, had caused approximately1.6 million deaths, almost exclusively in developing countries.

By 2010, GlaxoSmithKline and Pfizer had announced a development of a pneumococcal vaccine under the AMC program. According to estimates, this vaccine would have averted approximately 1.5 million deaths among children by 2020.

Despite this success, the concept hasn’t been replicated for other diseases. Owen admits that it is difficult in binding donors for a long-term commitment to buy these vaccines years from now. Owen points that negotiating a legally binding contract was critical in the case of pneumococcal vaccine.

Another challenge which Owen notes is the “distant lack of enthusiasm from disease researchers from bringing the drug companies in.” Referring to researchers who rely on grants to explore vaccines for diseases prevalent in developing countries.

“You come on television and say that you will spend 1.5 billion of the taxpayer’s money, but the leading expert on the disease disagrees with you publically.”

AMC’s provides evidence that incentivising the market can work for solving key development challenges. But like most good ideas, it needs a lot of leg work, and even more, vibrant intellectual discourse among development thinkers.

Can markets work for development? AMCs show that they can. As long as we remember that it’s all about the incentives.

Originally published at the London School of Economics Development Blog here

Leave a comment